About five years ago, I wrote and published an article about writing adaptations for various media formats on Steemit that brought me loads of attention. Not only did more than 400 readers upvote it, but it was nominated for a few awards and also republished on many blogs. It also won the Curie Author Showcase award, which was a big deal back then.

Reading through my old Steemit posts, I decided to republish it exactly as it was back then (with minor editing) so that you can enjoy it here too. Most of it still applies today and will help you see why adaptations for books, games, and movies vary so much from the original.

WARNING: This is a long article with loads of info. Get your coffee/tea/beer ready.

The Magical Dilemma of Adaptations: To and From Games, Movies and Books

I am very privileged and blessed to have taken my writing talent as far as a published author, screenwriter, game writer, poet, publisher and journalist. It has been a rather exciting journey, one that I would not pass up for anything in this world. I have met so many others in the craft of writing, and it has opened my eyes to the bright blue world out there.

Since I have so much experience in each of the writing disciplines mentioned above, considering an adaptation from one to the other is easy. I know how each discipline works, and the adaptation comes as a natural process of moving from one system to the other. However, there is something that I like to call the Magical Dilemma of Adaptations. If you ever ask someone to adapt one of your novels to either movie or game, they will always cringe before either accepting or declining.

You see, as easy as it may be, adaptations are something to be feared for many reasons. This is why I chose rather to write my own Silent Hill novels than adapt any of the games to a book. It is why I am writing a Malum book series instead of adapting Diablo games, which is the main inspiration. The same goes for my upcoming Resilience novels, inspired by the Fallout 4 game.

And I’m about to spell out the art of adaptation for you… one item at a time.

1. The Retelling of a Story

There is a reason they call it an adaptation. It is the retelling of a story in a new form. A film screenwriter will never write the novel over word for word. All that is required is that he or she carries the essence of the novel over to film. The same applies to a film-to-game adaptation. As long as the main plot is maintained, everything else is fair game.

And this is the crux of the matter. You will hardly ever find that a story is carried over exactly the same. Those Harry Potter games you played… I’m sure you’ve done way more things than Harry ever did in the books or films. But the main essence of the story was still there in the main quests and the action video sequences.

You see, the craft of each discipline is so very, very different. We will be getting to formatting at a later point, but for now, let’s explore the telling of the story.

With a BOOK, if you are a planner like me, you usually plan out the story themes and characters, the scenes that will move the hero onto his main journey until the eventual final outcome at the end. You can explore many side themes and have the character interact with other characters if you want, but the chapters are built up on suspense.

You want the reader to page to the next chapter in excitement, keeping them awake at night as they cannot put your book down. So each chapter’s words are wonderfully woven together to paint those intricate images in the reader’s mind. There are loads of descriptions and an immense amount of internal and external dialogue. You can spend 1 or 10 pages explaining how a mountain looks. It’s all up to you.

Main Point: You are telling a story to READERS for them to enjoy.

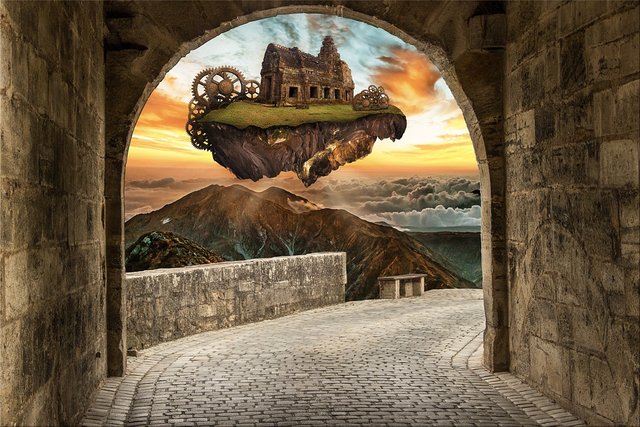

With a FILM, the luxury of telling a story is slightly diminished, in my opinion. Instead of long descriptions and expansive dialogue, you have to fit your entire movie into 3 or 4 Acts. Instead of chapters, your main focus becomes pitch points, major turning points from one Act to the other, revelations that pull your heroes into the final act, and then the actual showdown that ends the film.

I’m, of course, oversimplifying for the sake of my example, but the story is driven more by pulling the viewer into the visual element of the story than focusing on the beauty of the written word. The structure of the screenplay is the main critical driver for how the story is told.

Main Point: You are telling DIRECTORS and ACTORS how to portray your story on screen.

With a GAME, we enter a whole new arena of storytelling. A game is never really truly about the story, but rather the game mechanics, graphics and sound, and the pure joy of playing the game. Yes, the story should be critical, but I can write a large volume on games that either had no story or that was very pathetic. And why is that? Because someone had a great idea of what would make a great game, decided what the game should be like, and the story comes afterwards.

Most of the time, the guys who came up with the idea also make up the story for the game, and do not employ actual storytellers or writers. However, having said that, the best stories are the ones that revolve around an actual story or lore, such as Witcher 3, Elder Scrolls and the MMORPG I am writing for, Antreya Chronicles. These developers know that story is key and is what will pull the player in, and build the graphics, sound and mechanics around the story and lore.

Main Point: You are telling Developers and Designers how to create the gaming world in which your story takes place.

And this is where the adaptation magic comes in. As a game writer adapting a film or book, you have so much more scope to explore not only the main story but some side quests too. In films, you get to visually portray a story to viewers. In books, you can flesh out characters and locations, creatures and mythology. They are all beautiful in their own way.

The adaptation dilemma comes in the fact that each has its own way of telling a story. Which brings me to my next point.

2. The Length of a Story

This is the main issue of adaptation that causes problems and has film critics saying, “That was nothing like the book”, or game critics saying, “Where was that in the movie?”. Each discipline has its own set of rules when it comes to the length of a story. This becomes critical when doing adaptations, but before I get to that, let me explain how the ‘length rules’ work for each discipline.

BOOK: The usually acceptable standard for the length of a book depends on what your goal is. Here are the book lengths and categories I usually rely on, but they do vary across the world:

Novel: 40,000 words or over

Novella: 17,500 to 39,999 words

Novelette: 7,500 to 17,499 words

Short story: under 7,500 words

Now, in my publishing company’s anthologies, we have short story anthologies with limits of up to 10,000 words, whereas we categorise novelettes up to 20,000 words. These are mere guidelines, really.

Now, usually, it is accepted that Novels usually reach between 80k and 120k words. If they reach over that, then the reader can become disinterested in reading any further. Of course, there are exceptions. Epic Fantasy, which is known for stories based on massive long quests, will expect way beyond this point.

Case in point, my Celenic Earth Chronicles epic fantasy novels reached about 500 pages each. For me, a book needs to be greater than 300 pages for me to really enjoy it. And I prefer series of books rather than standalones.

We will get to later why the number of words is essential for book-length, but….

Main Point: Length is based on NUMBER OF WORDS

FILM: For the purposes of this article, I am only really focusing on feature films. However, I will name other types of films in this section, as length relates to them too. A good, hard, fast rule used by Hollywood is that each page in a screenplay roughly equates to 1 minute of film time.

So, a two-hour movie would have to fit in a 120-page A4 screenplay manuscript. A comedy series of 30-minute episodes would have to be done on a 25 – 45 page script per episode. A drama episode like Game of Thrones that is roughly 45 mins to an hour long would fit nicely in a 45 – 60 pager.

Main Point: Length is based on NUMBER OF PAGES

GAME: Now we come to the most expansive medium of the story… ever. There is no limit on how many words can be used, or how many pages are used in a game script. There is no law that says an 8-hour game will take about 480 pages of script to write. Not at all. And why is that?

Because the script does not only contain the story. We will get to this in the format section soon, but in a nutshell, it also contains many of the gameplay mechanics you will find in the game. There is the lore or background of the game story, there are items to be included, magical abilities and levelling up, quest items, random loot, character descriptions, NPC descriptions, and NPC random dialogue, etc.

And, the script is never written in one setting. With a book, you write one draft and rework that until it is perfect. With a film, the same applies to a script. With a game.. very different. You will write the main story out. Then later, you will add side quests, dialogue, extra items, etc. Then, you write the next part of the game. It is an ever-evolving story that follows the main game overview until the final end is reached.

Main Point: Length is based on GAME CONTENT.

Now, when it comes to adaptations, this is where the dilemma comes in. Imagine taking my Silent Hill: Betrayal novel of 470 pages and adapting that into a 120-page film (which I am currently doing, btw). Imagine taking something that took you hours or days to read and fitting that into a 2-hour film.

This is exactly the reason why critics complain the Silent Hill movies were nothing like the games. Excuse the fact that they changed main characters and lore, they had to stick to three acts, strip the game story to the bare minimum and keep it to a short movie length.

The same goes for adaptations to games. If you have watched any of the Lord of the Rings movies or read the books, you will know that never do the heroes ‘level up’ and acquire new abilities. The Lord of the Rings games can carry on for a few days if you really try and do everything there is to do and acquire all the PS4 trophies or Xbox achievements.

And imagine Bethesda had actually given me the right to adapt Skyrim to a book (here’s still hoping). I would love to fit as many side quests in, such as the Thieve’s Guild and The Dark Brotherhood. But having to restrict the book to a certain amount of words so I don’t end up with a 1000-page novel, the best I can do is have my hero run into members of those guilds.

So you see, length is one crucial element as to why adaptations will never be as pure as the main source. Formatting is another.

3. Format of the Story

I cannot express enough how formatting has a monumental effect on the telling of the story, but I am going to try. If, as a novel writer, you think you can just cross over to writing screenplays the same way, let me warn you now that you are in for a very bad experience.

If Directors ever catch you writing screenplays the way you do novels, they will either throw it out and put you on a blacklist, or ask you to rewrite the entire script. Games have a small bit more leeway, as sometimes they just have writers to write the main story, and another group writing the items and dialogue that need to be added later on.

However, it is essential that you understand the format of each discipline so that you can see why adaptations can be a nightmare in this regard. Length is still relatively acceptable when compared to formatting differences. Let me explain.

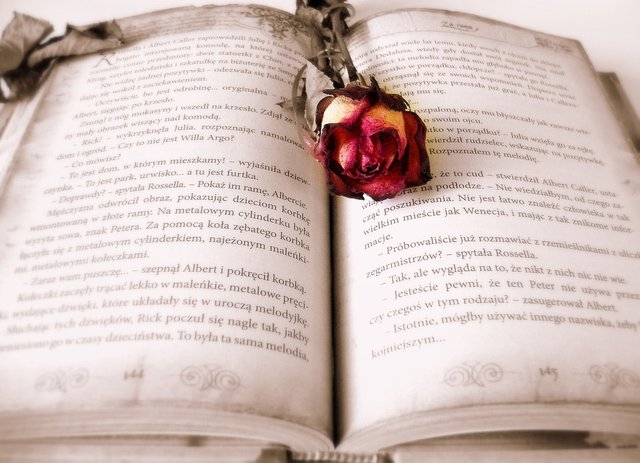

BOOKS: Stories are written in prose form. In other words, stories are conveyed over chapters, sentences and beautifully descriptive words. Paragraphs are aligned in a certain way to be appealing to readers. Stories are judged by grammar, spelling mistakes and the way the story has been told in written format. Are chapters long enough? Is there a hook at the end of a chapter? Did you describe the character long enough?

And then there is internal dialogue. You can share the characters’ thoughts with the reader. You can show and hide deception very easily. Suspense is built up by what you write and what you choose not to reveal until a later stage. You can describe so many elements just as you want, as long as it sounds realistic and logical. Here’s an example of writing in a novel, which I will carry over into the other disciplines.

Johnny held his breath. The clicking sound of the creature’s hooves resonated around the side of the wall, inching its way closer to him. Johnny gripped the dagger in his side, ready to strike when the time was right. He knew there was no making mistakes, it was crucial that he drive the dagger straight into the beast’s third eye.

“Come on, you ugly thing,” Johnny whispered. “Almost there.”

He heard it shift towards him and jumped, blade held above his head. When he drove the blade down, there was nothing. Any sound or sight of the beast was gone. He squinted into the dark passage, wondering where it had gone.

Ok, so that’s not my best work, but I wanted to highlight some items under films so you can see the difference.

Main point: The Story is woven into DESCRIPTIONS of what is happening for the READER to VISUALISE.

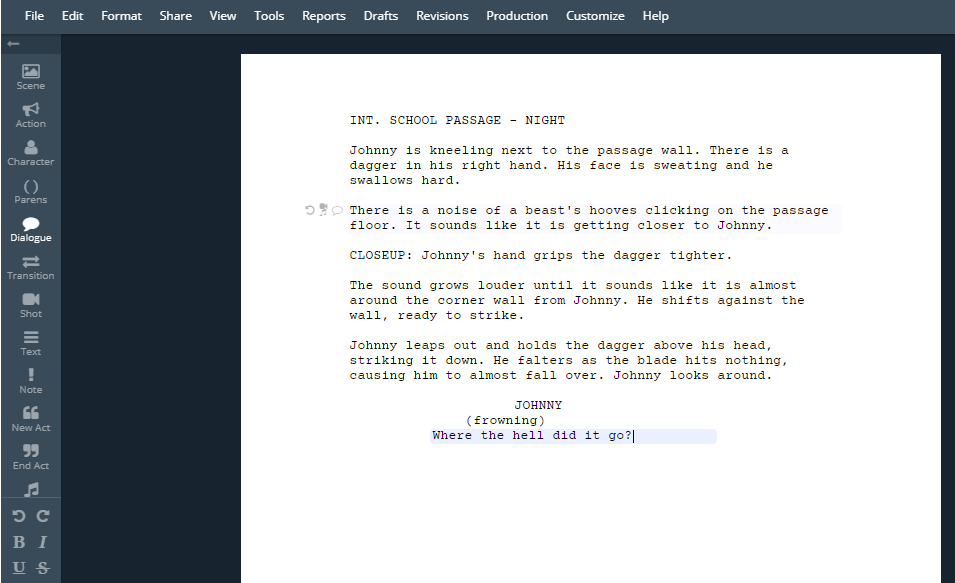

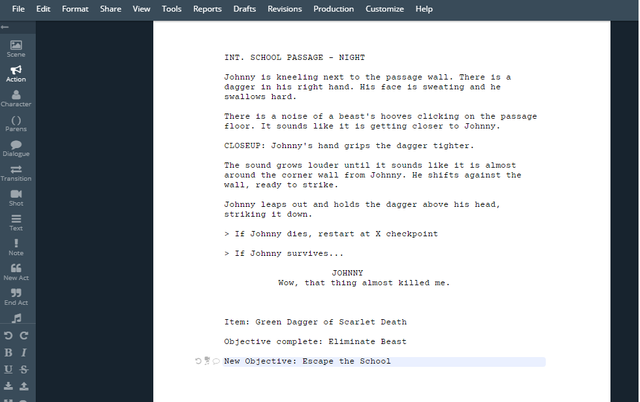

FILMS: Films have a completely different aspect to them. If you have never seen a film script before, let me explain. There is only one really acceptable standard for film script formatting, and that is usually the one that Hollywood accepts. Programs like Final Draft and Writers Duet (online) are already set to this formatting, so all you have to do is write. Basically, these are the essential elements of a script’s format.

SCENE: You tell the director, producers and actors if the scene takes place inside or outside, where the location is and what time of day it is.

DESCRIPTION: You tell the director, producers and actors what is happening in the scene. You cannot write this part like a novel. You have to basically tell them how everything is to be acted out on the screen to portray the story. You cannot write “Johnny was wondering…” because there is no way to show the viewer that Johnny is wondering anything, except to squint profusely.

DIALOGUE: You tell a certain actor that he now has to say or do something.

And as an example of the formatting:

The only way the audience knows what Johnny is thinking is if he says it out loud. They will not see this script. They will not care if there are grammar or spelling mistakes. The only thing the audience cares about is how well the actor on the screen is acting.

Main Point: The Story is Translated into ACTIONS for the VIEWERS to SEE.

GAMES: Once again, games are extremely different in formatting. Yes, it is similar to a film script, but there are so many elements added to it, that calling it similar to a film script can be quite insulting. For some games, writers actually write the plot out like a novel and then transcribe it into script format.

It depends on how fussy the game developers are really. But, as mentioned before, the story isn’t really the real part the developers focus on. And the best way I can describe this is through another example. And for this example, let’s imagine there actually was a beast on the other side of the wall and let’s get creative.

Ok, yes, I have completely oversimplified this, but I hope you get the point. Further to this, should the player enter a village, we would have to write NPC (non-playable character) dialogue for anyone the player may come in contact with. Then there are the behind-the-scenes things, like should Johnny level up at this point, and what stats and abilities could become available to him. Etc, etc, etc.

Main point: The Story is driven by QUESTS for the PLAYER to COMPLETE.

So how does formatting affect adaptations? Besides the fact that you have to write it differently, you also have to convey the story in a very different way from the book, film or game. When writing a novel based on a game, you have to rid the story of all the extra additions and side quests that have nothing to do with the story, and flesh out the main storyline.

With games to film adaptation, the skeleton is ripped bare even further, and the actors are told how to portray that story on the screen. Adaptations are not easy, and rarely are they done right.

4. The Characters and the Audience

Perhaps the most essential element of whether the story will be a success or not is derived from the portrayal of your characters and the audience. I’ve touched on some of these aspects already, but is important for you to understand why adaptations are so different from the source material the next time you judge them.

BOOKS: Characters are described in detail, sometimes excessively, so that you can visualise in your head what they look like. Even with the best descriptions, readers all over the world will have a very different view of characters than what was originally intended.

Your audience reads the words that are written on the pages and is expected to imagine in their heads what you are talking about. And the way you describe it in words can amount to the failure or success of your novel. You have a personal relationship with your characters, though.

Main Point: You have FULL CONTROL over your CHARACTERS and how the READERS should IMAGINE them.

FILMS: Here, characters are displayed on the screen by actors. Visual stimulation is everything. The character’s visual looks and actions should tell you what kind of person they are. No words are going to appear on the screen to explain that to you.

As a writer, you actually have a small amount of control over this by describing to the director what the character is like, BUT the director and producer have the full power to decide what they will be doing, how they will be acting and what expressions they should display.

Your script is seen as a ‘guideline’, but when the film is being made, the director will enforce what happens on screen. This is called Creative Licence. And this is where things change from what happened in the source material.

Main Point: You have MINOR CONTROL over your CHARACTERS and how the VIEWERS SEE them.

GAMES: You would think you would have some control over your characters, but really in many cases, you don’t. If you get signed on to write for games, usually, the developers will tell you what characters and traits there must be. And you need to develop the story around them. If you’re adapting to games, the characters are basically laid out for you already, but again Creative Licence kicks in.

Battle scars that weren’t in the movies, powers and abilities added that were nowhere in the books, etc. Where was there ever a pink lightsaber in Star Wars movies? Anyway, the list goes on. Games are all about content, content, content. For instance, the Unicorn in Assassin’s Creed Origins. Creative Licence, everyone.

With RPG games, there is almost no point describing characters, since, in many games like Skyrim, players can change how they look and what clothes they wear. Yes, you can make a list of all available items and looks, but this will largely be left to the graphics department.

Main Point: You have LITTLE or NO CONTROL over CHARACTERS and what PLAYERS DO with them.

Now, before I end this section, let me just explain about adaptations. Yes, with adaptations, you don’t really really control characters’ traits in books without sticking to the main movie or game source. However, you have the ability in books to be more creative with your descriptions to give your character an edge or to build suspense.

In movies and games, suspense is built differently and is triggered by different events. And when adapting from books to movies and games, translating those characters to the screen is a very different experience.

5. The Writer’s Value and Relationship With the Audience

I wanted to add these small sections, especially for my fellow writers reading this, so that you can understand the relationship you have with the audience of your work. Many do not know this from the outset of being assigned a project, and later when it happens, you may be slightly crushed. It is something you should be aware of, especially when it comes to adaptations.

Let me start with the usual writer relationships, and then reveal the difference with adaptations.

BOOKS: As a writer, you have a direct relationship with your audience. Readers will read your work and criticise you openly, either positively or negatively. There will be constructive or destructive criticism. Sometimes destructive criticism can be very debilitating. And many of the readers will share their views online, which can be both good or bad, depending on the reviews.

When adapting to a book, the reviews are less about how good the story is and more about how well you adapted the story to the book. Be prepared for this, as this will have a direct effect on you and whether you decide to do adaptations ever again. Sometimes it is better to write a new story based on a gaming world than to adapt directly.

Main Point: You have a DIRECT relationship with your READERS and it is CLEAR you wrote the book.

FILMS: Unless you are a reputable screenwriter, where people will say, “OMW, the guy who wrote RESIDENT EVIL movie will be writing the new SILENT HILL film!!”, there is little chance people will know who you are. Films are praised for their actors, directors and producers.

There have been occasions where writers have been praised for a great story in a film, but that is not the main focus of films. Rather, it is how the story is portrayed on screen. Most often than not, a screenwriter’s original script is raped by a director or producer and a new final version is made that looks almost nothing like what you wrote. The audience comes to the cinema to watch the actors, not read your script.

When it comes to adaptations to film, there is more of a chance for you to be noticed. The fans who have read the books or played the games will be eager to know who is writing the adaptation to film, and will instantly google who you are and your history before you even write one word. They want to make sure you won’t mess up their favourite game.

Yes, when they come to the cinema, they will still pay attention to what the actors do, but there may be a comment like, “Hey, what happened to that super cool plasma gun he was supposed to shoot through the toilet wall?? That was the most important part of the book!!”

The fact remains, though, it may have been the director who chose to kick that out of the script because of the Creative Licence. So:

Main Point: You have NO relationship with the VIEWERS and it is NOT ALWAYS CLEAR you wrote the script.

GAMES: With games, there is a slightly better chance for you to be noticed as the writer than for films, but not as much as books. In game development, you usually have a team of writers working on all the things that need to be written down. Quests, side quests, NPCs, main characters, magic, abilities, etc. You also have more control over what is said in-game and what objectives are to take place.

In my opinion, you will have more fun adapting from a book or film to a game. You have so much more scope in what you can do. However, unless you are a famous writer, players will be more interested in content than the actual story.

You have a better relationship with players than a film audience, but I doubt many will ask during the credits who wrote the script for the adaptation. They would be more interested in which game developer is taking on the task than which team of writers were assigned.

Main Point: You have a PERSONAL relationship with PLAYERS who play your quests, but they probably won’t know who YOU are.

I have found in my limited experience that game writers stand out the most when either: 1. The game sucks so much, but the story was great or, 2. The game was awesome, but the story sucked. It is usually in these instances that critics ask, “Who wrote this game?”

6. Knock-on Effect of Adapting Story Elements

Before I get to my conclusion, I have to touch on something that is most probably the most vital reason why critics say, “This is nothing like the original” (or insert your own criticism here). It is what I call the ‘Knock-On Effect of Story Adaptation’. It is something the readers, viewers or players are blissfully unaware of and what we writers have to suffer through.

When we adapt, we sometimes have to add to or take away something from the story for the sake of continuity. As mentioned before, films have to be kept short. This means, taking the skeleton of the story and fitting it into 2 hours of film. We have to throw away something that may be important to you as the book reader or game player just so that we can keep the base story in.

For books, we made need to add something to make the actions seem more logical. In a game, you can just blast a beast with your fire magic. In a book, we have to describe that. You may choose to kill the boss with your spiked club of mass destruction, but in a book, we might have to use something that makes a bit more sense.

And this is what causes the knock-on. Once we remove an element from a film, then it causes a problem for the rest of the film. Let’s say we remove a creature that we do not consider essential to the film. When an event happens later in the film where that creature would have passed a special weapon to the hero, instead, one of the characters that have been beside him all along will pass that weapon.

This has happened in so many movie and book adaptations, that it has caused an outcry in many instances. Remember also that film directors and game developers have to stick to a certain budget. So for films, they can only employ so many actors, which means sometimes side characters get cut out for that very reason. So now, Bob will be the one that kills that stingray instead of Norman.

This is just the nature of adaptations. It is something that you as a writer must just accept sometimes, and which you may unfortunately be heavily criticised for, even if it was the film producer or game developer’s decision.

CONCLUSION

What started out as a small post really grew into something massive. And this does not even cover all the elements of story adaptation, but it is something you need to be aware of if you are either a writer wanting to adapt or part of the audience that thinks adaptations suck balls. Also, please note that this is all my own point of view from my own experience. Many writers may disagree with what I said, but I stand by it until I learn differently.

I really hope you enjoyed this post and it enlightened you a bit about the world of adaptations.